The Story Behind The Song

Most songs age; decades later they feel dated and time-worn. Yet occasionally a single is released that resists the cultural erosion of passing fashions. Sounding as fresh and immediate as the day they were recorded, these are the amber songs, timeless jewels that are perfectly preserved to be appreciated by any generation. This is true of Video Killed The Radio Star. Its flawless arrangement and production have created a peerless exemplar of mainstream pop that has rarely been eclipsed.

Inspired by J. G. Ballard's The Sound-Sweep (1960), it's a poignant song about a radio star whose career is ended by the advent of television and video. In his sci-fi story, Ballard writes about a time when traditional audio has been replaced by ultrasonic music, which directly stimulates the audio centres of brain to provide a more profound experience. The enormous back catalogue of audio music is being re-written ultrasonically without the need for singers. The story centres on a discarded opera diva who is slowly going insane. Living in an abandoned radio studio, every night she thinks there is a hostile audience booing and catcalling which only strengthens her deluded ambition to appear on stage one more time. By blackmailing the magnate of Video City she gets a prime-time television slot. But when her moment of redemption finally comes she sings like a banshee. The audience boos and catcalls.

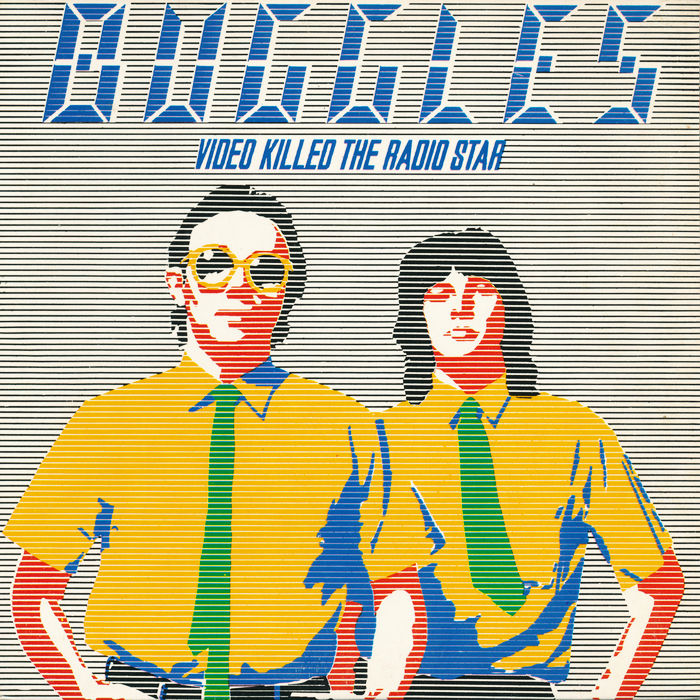

Now back to the song. The lines "And now we meet in an abandoned studio" and "Rewritten by machine and new technology" could have be lifted from Ballard. In the lyric a 1950s radio star replaces the opera diva, and video technology, which the writers (Horn, Downes and Woolley) correctly foresaw was becoming the dominant force in the music industry, is the reason for the radio star's demise. The genius of the production is the modulation on Horn's vocal that gives it a remote, old-radio quality while the breezy backing vocals, panned left and right, add a radio jingle melody.

The song has a global appeal – it was number one in sixteen countries, staying at the top in Italy for nearly half a year. As Downes reflected later, "in those crazy, hazy months between 1979 and 1980 we achieved a place in pop history." They also wrote, recorded and released the underrated album The Age of Plastic, which continued to explore the impact of technology on our lives. The album did not live up to the massive expectations of the record label, the next singles flopped and within six months Horn and Downes said "no" to The Buggles and joined Yes.

It's surprising that the group that foresaw the importance of image in the music industry should have cared so little about their own. The Buggles brand was dreadful – a parody of the Beatles, it was intended to contrast with the anarchic names of punk bands – and the video portrayed the group as goofy. "In those days I never really thought much about packaging or selling myself, all that really concerned me was the record," said Trevor Horn. Focusing exclusively on the sound and neglecting the group's identity was an error that may explain why Living In The Plastic Age was not as successful as it deserved to be. Indeed, the video of Video Killed The Radio Star may have helped kill The Buggles and their extraordinary song was a prophecy of their own demise.

And that's a story line that might have come from J.G. Ballad himself.

We hereby instate Video Killed The Radio Star by The Buggles on The Wall as No.6 Best Single of 1979

Not only was it incredibly prescient about the upcoming MTV revolution, it is simply a timeless, stunning, pop classic.Dave B